- Home

- Priest, Cherie

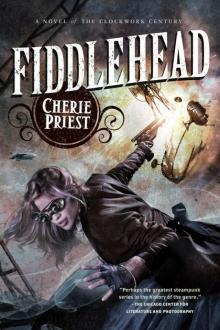

Fiddlehead (The Clockwork Century) Page 4

Fiddlehead (The Clockwork Century) Read online

Page 4

A memory flickered at the back of Grant’s mind. He’d heard something that morning, part of a briefing that had piqued his interest. “The science center? They told me there was an explosion last night during the party.”

“Correct.”

“And you have people working out there, don’t you? That scientist from Alabama?” They’d met once or twice in passing at the Lincolns’ house. Grant recalled a quick, impatient colored man, with eyes too old for a man still in his thirties.

“Gideon, yes. That’s him. He was there when it happened.”

“Dear God … did he survive?”

“Oh yes, yes indeed. Some of his work was lost, but he saved as much as he could. Quite a lot of information, considering.”

“That fellow’s research … what was it about, again…?” Grant rooted around in his memory. “He’s teaching a machine to count, or something like that?”

“Something like that.”

“Oh, wait, I remember: He was building a machine to solve all the problems that mankind can’t. Once upon a time, you would’ve argued that there were no such problems. You were such an optimist, Abe. You believed we could do anything.”

“I still do,” he insisted softly. “Mankind remains a marvel; and this machine was built by a man, after all.”

“True, true. Did it work? Can it count? Or was it destroyed in the explosion?”

“It worked.”

Grant shifted forward, his elbows on the tops of his knees, the glass still perched in his hand. “Did you ask it … did you ask…?”

“We gave it all the known parameters, variables, and information points we could find—everything from disease figures to population density, weather patterns and industry, money, trade, and commercial interests. And then I asked your question—our question. The only question worth asking a machine of its caliber. I asked the Fiddlehead who would win this conflict, and how long it would take, assuming no new variables are introduced.”

Lincoln hesitated, and a brief spell of silence settled between them.

Grant did not break it. He was afraid of the answer, knowing it wouldn’t be a good one—and feeling as if he’d asked a gypsy’s magic ball for military advice.

What would a machine know, anyway? How could nuts and bolts, levers and buttons, tell him how to fight a war, much less how to end one? The president was a man of instincts and suspicions, and he understood the flow of battle like a riverboat captain understood the surge of the Mississippi. He could take the pulse of an altercation and listen to the rise and fall of artillery, coming and going like thunder. He had known war firsthand, many times over—and that knowledge had brought him to the nation’s highest office and kept him there for three terms, because men believed in his instincts.

This time, Ulysses S. Grant was terrified that his instincts were right.

He cleared his throat to chase the tremor out of it. “Well?”

Abraham Lincoln withdrew a carefully trimmed packet of papers from a satchel on the side of his chair. He sorted through them, picking out two or three sheets and tidying them before handing them to his friend. “As far as the machine can tell, the United States of America will end. But it won’t be the war that breaks it.”

“I beg your pardon?” Confused, Grant took the pages. They’d been cut by scissors, as if pared down to size from a longer piece of paper. It felt like the onionskin of newsprint, smeared with inky fingerprints and smelling faintly like wet pulp.

“The North won’t win, Ulysses. And the South won’t win, either.”

“You’re not getting all philosophical on me, are you?”

“No, I’m not. There’s another threat, an indiscriminate one. One that maybe…”

Grant lifted an eyebrow and peered over the paper. “Maybe? Maybe what?”

“That maybe can’t be stopped.”

The president quit trying to decipher the papers and returned them to his friend. He didn’t understand any of the abbreviations, or the columns of numbers that covered the sheets from margin to margin. If this was a record of war, it wasn’t one he could read.

“What are you talking about, Abe?”

“We’ve long known that disease can turn the tide of a war more easily than strategy. Cholera, typhoid, smallpox—name the plague of your choosing, and it can devastate an army more effectively than any mere man-made weapon.”

“Hold on, now … are we talking about the stumblebums?”

He lifted one long finger aloft. “Yes, well done. The stumblebums. That’s one word for them.”

“Guttersnipe lepers, I’ve heard that too.”

“Leprosy isn’t the worst possible comparison.”

Grant waved his hand, dispelling the idea, and splashing his drink in the process. “Goddammit,” he grumbled. While he blotted at his pants with his handkerchief, he said, “But it can’t be. We have doctors working on that problem, even as we speak. Entire hospital wings dedicated to the investigation and treatment of the issue.”

“Entire wings, yes. Filled with violent, dying men. Eating up resources, even as the situation worsens.”

“We’ll get it under control.”

“Do you think so?” Lincoln asked. “These numbers tell us otherwise. The epidemic is spreading exponentially, turning a small vice of war into something big enough to bend the arc of history. You could call it a self-inflicted and self-defeating problem, except that when these lepers get hungry, they bite; and their bites become necrotic with deadly speed. One lone leper can kill dozens of healthy men. Perhaps hundreds. God only knows.”

God wasn’t the only one who knew, Grant thought bitterly. Desmond Fowler’s clandestine program probably knew it, too.

“It is thought,” Lincoln continued, “that there may be a secondary cause of affliction—something unrelated to the drug itself.” He paused to watch Grant’s reaction, but Grant didn’t give him one. “But there’s still so much we don’t know.”

“Then tell me what we do know. Or tell me what your Fiddlehead knows, at least.”

Lincoln looked down at the pages again, then withdrew a pencil from his satchel. He pressed a button to activate his wheeled chair and brought himself closer to the president, pulling up alongside his seat. The firelight warmed and brightened them both and made the brittle paper look brighter than a lampshade.

Lincoln circled one column’s worth of information. “You see this part, here? These are casualty figures from three skirmishes two months ago. None of the field doctors reported any lepers, or any drug use among the men.”

“I see,” Grant said. But he didn’t.

“The numbers are precisely what you’d expect: Half of the men died from their wounds. Of those who remained, approximately half succumbed to known diseases or infection. These other men”—he pointed at a secondary line—“were too badly hurt to return to battle, but they did survive. Now, look at these figures, over here.” He drew another circle. “These are numbers from four other skirmishes around the same time. Two in northern Tennessee, one on Sand Mountain in Alabama, and one outside of Richmond.”

Grant took a slow, deep breath and let it out again as he read the Tennessee casualty figures. Fifty percent dead from injuries. Two percent injured beyond further combat. Forty-eight percent …

“Forty-eight percent dead … from what?”

“From necrotic injuries, inflicted largely by their fellow soldiers.”

“What on earth have those Southerners done?”

“It’s not just the Southerners.”

“These are all Southern battlefields!”

“Most of the battlefields are Southern battlefields,” Lincoln reminded him, using the gentle tone of someone who is dealing with a drunk. Grant didn’t care for that tone, but he ignored it. He’d heard it from everyone, for years. “And the Southern soldiers aren’t the ones chewing up our boys after the fact; these are our figures. Our men. That said, the Confederacy’s having problems too—the same problems, almost exact

ly. In fact, the only time the Fiddlehead balked was when we asked where the drug came from, North or South.”

“It didn’t know?”

“It didn’t say. Gideon says the question shouldn’t have been phrased that way, since it might have come from someplace else. Something about contradictory absolutes, he said.”

“So where did it come from, do you think?”

Lincoln shrugged, a gesture that made him look like a funeral suit sliding off a hanger. “The Western territories? The Mexican Empire? The islands? The machine couldn’t tell us the drug’s origin—only that the lepers will win the war.”

“Balderdash,” Grant spit. “It’s utter balderdash, and you know I mean no disrespect.”

“It’s science.”

“The war won’t be won by the walking dead, Abe.”

“And why not? Before long, we’ll have more soldiers dead than living—and when the dead outnumber us, the advantage is theirs.”

After a frustrated, uncertain pause, Grant said, “Your machine offers up more questions than answers.”

“Its vocabulary is limited. It can only work with what we give it.”

“It must be wrong.”

“It’s frightening, but I don’t believe it’s wrong. We can’t win, and neither can the CSA.”

The president laughed sadly. This was almost precisely what he’d told Desmond Fowler not ten minutes before. “Then what do you suggest we do?”

“The only thing we can do is stop fighting. Declare a cease-fire, call a summit. Explain the situation to Bragg and Stephens—they’re reasonable men, old men. And they’re tired of fighting too.” He sat forward with some difficulty, and the firelight played across the sharp-cut angles of his cheeks. “You can tell them that we do not ask their surrender, and do not offer our own. Explain the greater threat and extend a hand of brotherhood. Not North against South, but living against dead.”

Grant shook his head. “It would never work. They’ll never believe us.”

“They might. When we asked the Fiddlehead to tell us how the war would end, we had to estimate figures on the Southern side—we didn’t have the precise numbers of living, dead, sick, or wounded. It was funny, really—or, rather, Gideon thought it funny: The machine accused us of lying to it.”

“How’s that?”

“It rejected our estimates as implausible, and supplied its own calculations. But we have every indication that the South suffers from the leper problem too, perhaps even worse than we do. We may get lucky: They may want a way out of the war as badly as we do, and if they’re aware of the threat in their own land, they might be open to a conversation.”

Grant harrumphed and scowled into the fire, as if he were asking it for a second opinion. “What if we could get Southern casualty reports? Send some spies out in search of accurate figures to feed into your machine. That’d give us a better idea of what we’re up against, wouldn’t it? It’d give us a hint about how open they’d be to … a conversation, as you put it.”

Lincoln’s good eye glittered warmly. “It might. But, as you’ll recall, there was an explosion last night—speaking of spies.”

“I’m sorry, come again?”

“Two men,” he told him. “If not spies, then mercenaries—sent to destroy the Fiddlehead, and kill the man who’d created it. From Gideon’s report, I doubt either one of them would’ve thought to make the attack alone. Someone paid them to make the effort.”

“Any idea who?”

A slow, knowing smile spread across Lincoln’s crooked face. “Who? Not precisely. But I appreciate that we both understand the why, and that we choose not to insult one another by pretending.”

“You want to blame warhawks like Desmond, or his brethren on the other side of the line. But why would they go after your calculation machine? How many people even know it exists? How many people would put stock in the conclusions of a … a … a fortune-telling heap of nuts and bolts, assembled by a colored man? No one.”

“I may be permanently seated and long out of office, but I’m not exactly no one,” Lincoln replied stiffly. “Gideon’s work is sound. The machine is unprecedented, a marvel of science—and you just wait”—he waved one warning finger—“history will bear this out. The war has to end. We have to turn our attention to the leper threat. We must bury all the dead and see to it that they remain buried.”

“I can’t push a button and end hostilities,” Grant fussed … but again he thought of Desmond Fowler, whose clandestine program might do just that. “You can’t ask for such a thing based on a pile of paper that no one understands but you. And your team of tinkers,” he amended quickly. “I can’t go in front of Congress with the message that Abe Lincoln says we should all find some hobby other than war because dead men walk and we should do something about that, instead. You have to bring me more than this.”

Lincoln slumped back in his chair, his good eye narrowed. “I don’t have more. Not yet. And someone—perhaps a Southerner, perhaps someone in your own administration—is working hard to make sure I don’t come up with any additional evidence.”

“How so?”

“Because they went after Gideon, and when they couldn’t catch him, they went for his family. They’ve taken his mother and nephew—kidnapped the pair of them without so much as a note. Dragged them back to Alabama, I suppose. But I’ve called in a good man to recover them, one of the old Liberation Rangers. You’d know the name if I said it, but then you’d have to do something about him, so I’ll leave it there.”

“Ah. Then I can make my guess. I remember the old case well—nasty business, that. I appreciate your discretion. But as for the scientist’s family … you think it was a lure? Something to take him away from his work?”

“As likely as not. Gideon is the only man on earth who could rebuild or re-create the machine. Someone, somewhere, already knows what the Fiddlehead will tell us—and without that machine, it’s our suspicions versus their profit. Our word against theirs.”

“The word of a former slave—a political fugitive. It won’t carry much weight.”

“Then add the word of a former president. A political figure, instead. It will carry more weight than you think, and they know it. They’re afraid I’ll say something, but they’re unwilling or unable to come for me. So they reach instead for Gideon, thinking that I have nothing without him, and thinking that he’s vulnerable.”

“And I expect they’ll learn the hard way that he’s not.” Grant mustered a friendly grin.

Lincoln closed his eye. When he opened it again, it was to plead with him. “Yes, they will. But I need your help while I hold them at bay.”

“What can I give you? Money? Men? I know you don’t think much of the Secret Service, and neither do I sometimes … but they’re at our disposal.”

“Oh, no. I can’t trust them any more than you can. I’ll stick with the Pinks, if you don’t mind—they’ve kept me alive this long. Mr. President, my old friend … what I need is information.”

Three

Maria Boyd, sometimes called Belle and sometimes Isabella, stamped her feet and wished she was sitting closer to the big iron furnace in the corner of the room. She drew her shawl around her shoulders and eyed the empty desk beside the big iron hearth, where Andrew Kelly usually sat. He was away on assignment, and wouldn’t be back for a week.

One long, cold week.

“To hell with it,” she muttered. After all, no one was present to object: Rose Anderson was out of the office chasing down a murderer in Minnesota; Fred Williams was eyeballs deep in legal paperwork following that affair in New York last Tuesday; and Timothy Hall had been sent down to the jailhouse to bail out Percy Jones—who had gone and done it again, and might get fired this time, depending on the boss’s mood.

Only James Elders was left on the main floor of the Pinkerton National Detective Agency office. And yes, he’d probably notice if she moved seats, because he noticed every time she moved anything, and was not precisely subt

le about it.

Maria wasn’t worried that he’d tattle to Mr. Pinkerton, who probably cared less than anyone in the whole of Chicago, but she didn’t want to look weak. She hated looking weak like men hated looking foolish, and she worked studiously to prove that she was up to the same tasks as everyone else.

In fact, no one really doubted it. No one dared doubt it, because Allan Pinkerton himself had brought her on board last spring, politics and precedent be damned. If the old Union spy believed that the former Confederate spy was worth her salt, then everyone else who wanted a paycheck had best believe it, too. But that didn’t mean they had to be nice to her, so every day she worked to prove that she belonged.

But she didn’t belong.

Not in that office, typing up notes and filing signed papers, stamping the backs of checks and sorting telegrams like a secretary. Not in Chicago, either, where the heat-flash of summer suddenly gave way to a winter like nothing she’d ever known in Virginia. And Virginia got plenty cold, thank you very much … as she found herself reminding coworkers who teased her about her fingerless gloves and layers of scarves.

Not as cold as this, though. November on Lake Michigan, and the whole world might be frozen, so far as she knew.

On the rare occasions when she felt like defending herself, she insisted that there hadn’t been time to do any shopping when she’d accepted the job offer. She’d packed her things and caught the first train to Illinois, desperate to escape an increasingly unhappy situation south of the Mason-Dixon, where she’d come under scrutiny that stopped just shy of an allegation of treason. She’d married against advice, been widowed against her will, and, if it weren’t for the once-celebrated spy’s continued friendship with General Jackson, she might’ve met a court-martial in her mourning dress.

Adding insult to injury, she hadn’t been able to redeem herself yet, as she’d become altogether too famous for further espionage work.

Or any other work, as it turned out.

The CSA no longer trusted her, and the newspapers accused her of terrible things. What meager fortune her family possessed was lost in the war, her father’s hotel burned, rebuilt, and then seized for taxes under flimsy circumstances. He’d died shortly thereafter, and her brothers were dead, too, lost to the war effort. One sister had succumbed to cholera while working as a nurse in a field hospital. One served as caregiver to her husband, badly wounded at the second battle of Shiloh.

Fiddlehead (The Clockwork Century)

Fiddlehead (The Clockwork Century) Ganymede

Ganymede